A Machine With a Mind of Its Own

Ross King wanted a research assistant who would work 24/7 without sleep or food. So he built one.

For a machine that's changing the world, the device on the lab bench in front of me doesn't look very impressive - it just goes back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. A contraption about the size of a human hand moves from side to side along a track. At the far right end of its trajectory, a proboscis-like pipette pecks into a foil-covered plastic container and sucks up some liquid; the hand moves a foot or so to the left, and the pipette squirts out the liquid a few drops at a time onto a rectangular plastic platter covered with an array of 96 tiny depressions. Then it repeats the routine. Whirr, plunge, suck, whirr, plunge, squirt - a mechanical counterpoint to the cries of the seagulls outside the lab in this Welsh coastal town of Aberystwyth. The effect is oddly hypnotic. Ross King, a professor of computer science at the University of Wales and the Dr. Frankenstein behind this most humdrum of monsters, watches me watching it with a wry amusement that might mask a touch of embarrassment. "It comes across better on radio than on TV," he says.

Indeed, King's robotic lab assistant is something of an ugly duckling. High-throughput screening - testing vast libraries of chemical compounds on various types of cells to see whether they interact in ways that might be useful - has become a routine function in modern bio labs, and at the high end machines that do it are positively telegenic. For instance, the Automation Partnership, based in Royston, England, offers one that bobs, weaves, shakes, and stirs like a possessed bartender. Such uncanny dexterity costs roughly $1.8 million - but if you're a pharmaceutical company interested in performing as many experiments as quickly as possible, it's money well spent.

King's humble robot is based on a Biomek 2000, a low-rent fluid-handling device that goes for only $37,900. But it can do something its more nimble cousins can't. Its components - the tireless robot arm, an incubator in which cells cultured on the platter either wither or thrive, and a plate reader that examines the little depressions to see whether anything is growing there - are linked up to a much more exceptional brain. The artificial intelligence routines in that brain can look at the results of an experiment, draw a conclusion about what the results might mean, and then set off to test that conclusion. The "robot scientist" (King has resisted the temptation of a jazzy acronym) may look like a mere labor-saving gizmo, shuttling back and forth ad nauseam, but it's much more than that. Biology is full of tools with which to make discoveries. Here's a tool that can make discoveries on its own.

If this slightly faded town has any contemporary claim to fame, it's Malcolm Pryce's surreal pastiche-noir novels about private eyes and druid mafiosi, Last Tango in Aberystwyth and Aberystwyth Mon Amour. The University of Wales tends to operate well under the radar. It's a quiet hive of computational biology that benefits from small departments and relative isolation, conditions in which like minds are bound to find each other.

Ross King dresses in the black shirt, black jeans uniform that might be called goth geek, a voguish look in bio labs these days. He's soft-spoken and so even-keeled that his flashes of intensity aren't always obvious. But when he tells you that computers will surpass human scientific endeavor in every way, there's true-believer zeal behind the quiet Scots accent.

King came to the borderlands of information technology and biology by chance. When he was an undergraduate microbiologist at the University of Aberdeen in the early 1980s, no one in his class wanted to take on a computer modeling assignment offered as a final project. King literally drew the short straw, and soon he was programming the characteristics of microbial growth into a primitive mainframe. He has hardly looked back since.

Studying AI at the Turing Institute in Glasgow, he set about using machine-learning techniques to predict the shapes of proteins, one of the fundamental challenges of bioinformatics. King, though, found a twist. With his friend Colin Angus, whom he'd met at Aberdeen, he developed software that translated protein structures into musical chord sequences, one of which ended up as a track called "S2 Translation" on Axis Mutatis, an album by Angus' band, the Shamen. Later, at London's Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now called Cancer Research UK), he moved on to using AI to control the drug-related properties of various molecules. However, he soon found that his chemist colleagues weren't interested.

"We'd say, 'We want to make this drug to see if it will work,'" King recalls. "But we could never get any chemists to make the drug. They didn't explicitly say, 'Our intuition is better than your machinery.' They'd just never make the compound we wanted."

It wasn't until he moved to Aberystwyth in the mid-'90s that King found comrades who fully appreciated the potential of AI and machine learning. One of the first people he encountered there was Douglas Kell, a voluble, handlebar-mustached biologist with a clear view of where his field was headed. Kell felt that the piecemeal approach typical of molecular biology from the 1970s onward had been an unrewarding detour. The true aim of biology, he believed, was not the study of individual components and their interactions but a predictive knowledge of whole biological systems: metabolisms, cells, organisms.

In the 1990s, biology was poised to go Kell's way. Genomic research - using then-new hardware like the Biomek 2000 - was starting to produce data at a phenomenal rate, data that covered entire biological systems. That information wouldn't just challenge the capacity of molecular biology to explain what was going on molecule by molecule; it would highlight the inadequacy of the molecule-by-molecule approach.

Automation made it possible to find genes among the growing mountains of data, but it did little to illuminate how they work as a system. King and Kell realized they could begin to tackle that challenge by letting computers not only sift the data but also choose what new data should be generated. That was the key idea behind the robot scientist - to close the loop between computerized lab tools and computerized data analysis.

Once the goal was clear, the collaboration expanded. Steve Oliver at the University of Manchester, who had led the first team to sequence a complete chromosome, lent his expertise in yeast genomics. Another addition was AI specialist Stephen Muggleton, who had passed through the Turing Institute a few years ahead of King on his way to becoming a professor at Imperial College in London. He had worked with King before, and he, too, had been thwarted by chemists unwilling to follow up on ideas arising from his research. For King's team, making machines that could take the next step without human intervention was something of a declaration of independence (and perhaps just deserts).

By summer 2003, the robot scientist was fully programmed and ready to perform its first experiment. The team selected a problem based on a fairly simple and well-known area of biology - "something tractable but not trivial," as King puts it. The assignment was to identify genetic variations in differing strains of yeast.

Yeast cells, like other cells, synthesize amino acids, the building blocks of proteins that King and Angus had used to create their music. Generating amino acids requires a combination of enzymes that turn raw materials into intermediate compounds and then the final products. One enzyme might turn compound A into compound B, which then might be made into C by another enzyme, or D by yet another, while another turns surplus G into yet more C, and so on.

Each enzyme along the way is the product of a gene (or genes). A mutant strain that lacks the gene for one of the necessary enzymes will stall out, unable to continue the process. Such mutants can be easily "rescued" by receiving a sort of food supplement consisting of the intermediate substance they can't make themselves. Once that's done, they can get back on track.

The robot scientist's job was to take a bunch of different strains of yeast, each lacking one gene relevant to synthesizing the three so-called aromatic amino acids - three related chords - and to see which supplements they required and thus work out what gene does what. The machine was armed with a digital model of amino acid synthesis in yeast, as well as three software modules: one for making what might be called informed guesses about which strains lacked which genes, one for devising experiments to test these guesses, and one for transforming the experiments into instructions to the hardware.

Crucially, the robot scientist was programmed to build on its own results. Once it had conducted initial tests, it used the outcomes to make a subsequent set of better-informed guesses. And when the next batch of results arrived, it folded them into the following round of experiments, and so on.

If the process sounds familiar, that's because it fits a textbook notion of the scientific method. Of course, science in the real world progresses on the basis of hunches, random inspirations, lucky guesses, and all sorts of other things that King and his team haven't yet modeled in software. But the robot scientist still proved awfully effective. After five cycles of hypothesis-experiment-result, the automaton's conclusions about which mutant lacked which gene were correct 80 percent of the time.

How good is that? A control group of human biologists, including professors and graduate students, performed the same task. The best of them did no better, and the worst made guesses tantamount to random stabs in the dark. In fact, compared with the inconsistency of human scientists, the machine looked like a radiant example of experimental competence.

The robot scientist didn't start out knowing which strains of yeast were missing which genes. Its creators, however, did. So, from a biologist's point of view, the machine made no valuable contribution to science. But, King believes, it soon will. Even though yeast is fairly well understood, aspects of its metabolism are still a mystery. "There are basic bits of biochemistry that have to be there or the yeast wouldn't exist," King explains, "but we don't know which genes are coding for them." By year's end, he hopes to set the robot scientist searching for some of these unknown genes.

Meanwhile, the team is designing new hardware and software to upgrade the robot's mechanics. King and company received a grant to buy a machine like those from the Automation Partnership, one that can deal with far more samples and keep them from becoming contaminated with airborne bacteria. Then they would like to give the device's brain an Internet connection, so the software can reside in a central server and control several robots working in far-flung locations.

King has his eyes on different fields of science, too. The robot scientist's hypothesis-generating behavior might be just the thing for using pulsed laser energy to catalyze chemical reactions. Applying lasers to chemistry could be very powerful in theory, but variables like frequency, intensity, and timing are hard to calculate, and chemical reactions happen so quickly that it's tricky to make adjustments on the fly. A robot scientist's reasoning and reflexes would be quick enough to try lots of different approaches in a fraction of a second, learning what works and what doesn't through ever-better-informed guesses. King recently started testing this idea at a new femtosecond laser facility in Leeds.

For now, however, the emphasis remains on biology. Stephen Muggleton argues that the life sciences are peculiarly well suited to machine learning. "There's an inherent structure in biological problems that lends itself to computational approaches," he says. In other words, biology reveals the machinelike substructure of the living world; it's not surprising that machines are showing an aptitude for it. And that aptitude makes the machines a bit more lifelike themselves, developing plans and ideas - in a limited sense - and the means to carry them out. If you believe living things are uniquely mysterious, it's easy to imagine that fathoming the secrets of life would be the last intellectual quest to become fully automated. It may be the first.

Contributing editor Oliver Morton (oliver@dial.pipex.com) wrote about Hollywood stuntbots in Wired 12.01.

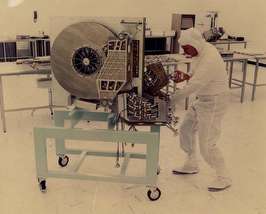

On Gizmodo, this stunning image an an ancient, room-sized hard drive being serviced by a guy in a clean-room bunny-suit. The best part is that this thing and a million of its brothers put together probably had a lower capacity than the USB memory built into the pen I last last month. Link

On Gizmodo, this stunning image an an ancient, room-sized hard drive being serviced by a guy in a clean-room bunny-suit. The best part is that this thing and a million of its brothers put together probably had a lower capacity than the USB memory built into the pen I last last month. Link